I just watched this movie, Meet Cute, starring (and exec. produced by) Kaley Cuoco and Pete Davidson, a Peacock digital streaming original.1 It has had a mediocre reception (57%/60%, two stars in the Guardian, two stars at rogerebert.com) but I liked it, and will thus be spoiling it here with a quick commentary. It’s a tight and expositionless 89 minutes. I love that about all the slightly off-centre lower-budget movies that end up on my Substack. They are efficient: Meet Cute has no subplots and is mostly dialogue between Sheila and Gary in the same locations. I suppose this material parsimony comes naturally to the time loop movie, since you’re just spinning it out of the same stuff repeated a bunch of times.2 They talk and talk, going through the same sentences in the same locations, allowing you to close-read them while you watch. It’s difficult to present the movie viewer with a direct repetition of prior material; the flashback sometimes allows this, but that risks its own lame clichés. The time-loop film insistently presents you with material whose significance is obscure, thus encouraging you to read it suspiciously, even to practice a kind of eidetic variation, in which the essence, not just of Punxsutawney Phil or some particular romance, but of bourgeois self-growth and the romantic comedy as such are disclosed to you.

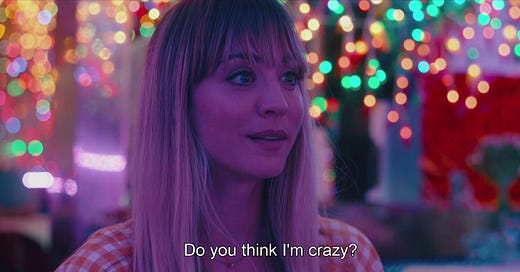

Meet Cute, unlike most time loop movies, and somewhat contrary to the critical consensus that it fails to escape the conventions of its subgenre, is not about being stuck in a time loop. Sheila (Kaley Cuoco) stumbles across a time machine in the form of a tanning bed in the back of a nail salon which allows her to travel back to any 24-hour slice in history she chooses. What happens is that she chooses to repeatedly confine herself to a time loop consisting of the previous 24 hours, so that she can repeat a perfect date she has with Gary (Pete Davidson) 365 times. It’s a twist on the form: she wants to be trapped! Sheila represents that tiny part of you that, when watching Groundhog Day, just wishes you had that much free time. She doesn’t actually have to accomplish any self-growth according to an unseen moral logic, or, indeed, defeat a bunch of alien monsters; she just has to choose to exit the loop.

This volitional repetition is a symptom. Sheila repeats the time she spends with Gary because she is severely depressed and is afraid that nothing in the future will bring her happiness. Eventually the ‘fifty first dates’ situation she has created for herself becomes tiresome, and she tries to fiddle with Gary’s actual life by jumping back to key moments in his upbringing and posing as positive role models or inserting formative experiences. She has noticed that he is a ‘passive’ man, neurotic (Pete Davidson is pretty good at this) and she wants to fix that, to file away the rough edges of her petit objet. Gary noticeably overreacts to small slips, screwing up his face and profusely apologising, swearing over and over again, when he drops a drink or Sheila’s phone, in what I felt was a strength of both the acting and of the film’s ability to break out of the romcom genre’s normatively equanimous tension level. It’s a break in their flirtatious patter, a brief on-screen vulnerability and hyper-sensitivity that is only calmed when Sheila embraces him and says “it’s OK for things to be messy sometimes.” Sheila’s interventions just make him into a macho jerk and so she goes back again and undoes them, thankfully without any further self-referential time-travel shenanigans, and we are back to the problem of Sheila’s temporal fixation.

That line, whose content is unconditional forgiveness, is the high point of the film’s attempt to tell a love story. There’s a lot of familiar and more-or-less mundane love and romance troping in this film, but this line elevates it, for me. Eventually, Sheila is able to convince Gary that the time-loop situation is really happening, and then Gary sneaks off to the time machine in order to perform his own intervention in Sheila’s life, to ‘fix’ her traumatic upbringing in some way, and thus end the loop that causes her to restart every date, after having derailed it by oversharing or pressuring Gary. This basically unspecified trauma partly stems from Sheila’s alcoholic father, who (we are repeatedly told) travelled from bar to bar until he died, victim to the meaningless repetition of an addictive pleasure. One question the film wants to ask is whether there can be some intervention into this species of bad infinity. One of the things Sheila repeatedly mentions to Gary on their first dates, for no clear reason at first, is that there was this cable guy who came to visit her house once who was really nice to her. This memory regularly returns to her unbidden, brief relief from her childhood memories of a pre-occupied mother and dead father, and we suspect it has something to do with her ambient sadness and magnetic attraction to Gary.

The time-travel-paradox twist of the film is that Gary is the cable guy. On their dates, they even find a blue-collar uniform shirt embroidered with the name Gary at a second-hand clothes stall, which Gary is still wearing when he finds the time machine. Gary’s intervention closes the loop of the film, and it also represents the high point of its Freudian embrace of a love that is more than Tinder romance. Gary time-travels to Sheila’s childhood apartment and finds that her mother is expecting him – she needs a cable guy to fix their television, buzzing uselessly in the living room. Sheila is in there, playing with blocks and pegs and stuff, and Gary worries that he has gone too far back: he actually says aloud that he thought he would find her when she was 16, 17, you know, when the important formative things take place, and that he could impart some emotionally settling message to her. But no, Gary is now face-to-face with this woman with whom he has been on a single date at the age of maybe 4 or 5. Whatever form his intervention takes will at least partly be obscured by the infantile amnesia that Freud described. The TV’s defunct ambient noise grows louder in the background and Sheila’s mother shouts indistinctly from the bathroom as she uses her hairdryer. Sheila gets distressed and begins to cry and sputter, as she literally attempts to stuff a round peg into a square hole in her set of wooden blocks. Gary is unsure what to do or how to calm her (or how to fix the TV), and he remembers the phrase that Sheila repeated to him on those multiple occasions where he began to melt down in expensive New York restaurants or on a ferry ride. The soundtrack does something interesting here, simulating a kind of bubble in which these overstimulating noises quieten, audibly distant. He leans into the bubble and says to the tiny Sheila, very gently and asking her to repeat after him, “it’s OK for things to be messy sometimes.”3

The intimacy and softness of this address by the man to the inner child of the woman is remarkable to me. The fact that it’s a short-haired, sleep-deprived Pete Davidson makes it touching and funny in its awkward everydayness. Meet Cute is a little undeveloped and clumsy, beholden to a lot of familiar turns, sure, but Cuoco and Davidson are excellent actors, and they tell a story that is finally quite raw and quite delicate and a little taboo and a little uncomfortable. It’s not really a time-travel movie; it’s a metaphor for finding the small person inside who wants to be spoken to. Love is a conversation between children.

I haven’t posted during November because I was working on my paper for the Australasian Society of Continental Philosophy conference, which has now taken place and went well, but you’ll have to let me know if you want to read the paper because it is not fun enough for Substack.

Groundhog Day (1993) budget: $14.6 million. Edge of Tomorrow (2014) budget: $178 million. Meet Cute budget: no idea, I don’t have an IMDbPro account. Let me know if you find out.

The proper name precedes the subject, and this particular feature of the symbolic order is maybe nicely metaphorised too by the frequency with which time travel films (note: not time-loop films) introduce objects which go back in time and then cause their own existence, raising the impossible question of where they first came from. Objects, or, indeed, signifiers, such as the all-important “it’s OK” phrase which Sheila tells to Gary, who then tells it to the very young Sheila in a psychically essential moment, so that she may then tell it to Gary again as an adult, for the first time. Nobody knows where the phallus came from and its signifying circle is grounded nowhere.