Notes on Chapter 4 of Fredric Jameson's Postmodernism

"architectural space is a way of thinking and philosophising" (125)

One of Jameson’s underlying threads in his book Postmodernism, or, the Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism (1991), made explicit mostly in the conclusion, is that the world of postmodern cultural production is primarily concerned with either a renewed emphasis upon or a sudden emergence of the ‘spatial.’ The strongest form of this thesis is his suggestion that “history has become spatial,” in the sense that all the disparate elements and concepts of our geopolitical environment, all the different countries, conflicts, commodities, actors, and so on, are cognitively compartmentalised, or in other words thoroughly decoupled from a total narrative, messily mapped in our heads by analogy with the unrelated but spatially contiguous political columns of a serious newspaper (374). This is arguably a payoff for the opening sentence of the book, in which the postmodern is provisionally defined as the age “that has forgotten how to think historically,” and which must, it seems, make do with thinking spatially (ix). The cure that corresponds to this diagnosis appears in miniature at the end of the first chapter and then more grandly at the end of the conclusion, and it is Jameson’s vision of “an aesthetic of cognitive mapping—a pedagogical political culture which seeks to endow the individual subject with some new heightened sense of its place in the global system” (54). This is a Utopian transformation of the symptomatic spatialisation that afflicts the subjects of postmodernism, who are condemned to ‘map’ history in a disjointed and meaningless way, and whose “technologies of the musical” (to take just one aesthetic example) have “already worked to fashion a new sonorous space around the individual or the collective listener,” thereby demonstrating that our period is marked principally by the “spatialisation” of its art forms (299). In the final analysis – which for Jameson, not unreasonably, is only a prolegomenon to some pedagogical praxis – this ‘cognitive mapping’ is “in reality nothing but a code word for ‘class consciousness,’” a completely new kind of dialectical emplacement of the subject within the map of their world, i.e. their relationship to the means of production and everything that entails (418).

This being the case, there’s at least one sense in which the architecture chapter of Postmodernism – which is actually entitled “Spatial Equivalents in the World System” – is the most important chapter in the book, which is funny, because it is also the chapter in which he uses the phrase “late-night reefer munchies” (98). This post is going to be a few notes on this chapter, with a primarily expositional aim.

buildings / poetry

How do you read a building? This problem is a microcosm of the hermeneutic challenge that Jameson faces at every step in this book, because the postmodern artworks he’s interested in all seem to be constantly flying apart and eluding any unifying interpretation, resisting any close reading, and then metatextually thematising the impossibility of interpretation as their only consistent formal feature. Buildings, in particular, suffer from a “problem of reference,” Jameson mentions, since buildings, “presumably ‘realer’ than the content of literature, painting, or film, are then somehow their own referent” (119). Buildings are only weakly and secondarily mimetic. What does the Frank Gehry House ‘mean’ other than ‘Frank Gehry lives there’? Jameson nonetheless suggests that postmodern architecture might perhaps be “the property of literary critics after all, and textual in more ways than one” (99). To make this plausible, we have to proceed through a transcoding allegory of architecture as linguistic and grammatical form, which then transforms into something more properly spatial by the end of the chapter.

This allegory dilates upon a brief moment in the standalone first chapter of the book, where Jameson is trying to ‘read’ the Bonaventure hotel for its postmodernism, and reflects that “I am more at a loss when it comes to conveying the thing itself, the experience of space you undergo when you step off such allegorical devices [the escalator qua machinic signifier of older promenade] into the lobby or atrium” (43). Here he struggles with vocabularies for different and opposing spaces that you experience firstly in a non-aesthetic way (you have to actually walk on the escalator), eventually arriving at a sense of the dialectical tensions latent or active in the competing spaces of the hotel as both functional and aesthetic, and the hotel’s own rejection of the ‘outside’ as one of its essentially (and negative) postmodern features. In the architecture chapter, we get a more comprehensive structuralism for this descriptive problem:

The words of built space, or at least its substantives, would seem to be rooms, categories which are syntactically or syncategorematically related and articulated by the various spatial verbs and adverbs—corridors, doorways, and staircases, for example—modified in turn by adjectives in the form of paint and furnishings, decoration and ornament … Meanwhile, these ‘sentences’—if that indeed is what a building can be said to ‘be’—are read by readers whose bodies fill the various shifter-slots and subject positions; while the larger text into which such units are inserted can be assigned to the text-grammar of the urban as such (or perhaps, in a world system, to even vaster geographies and their syntactic laws. (105)

This has some experiential plausibility to it – walking into the wrong building does feel like a sentence fragment – and at the same time is perhaps too fantastic an allegory. To be sure, Jameson immediately proceeds to disqualify it through historicisation: there is a real history of the social emergence of different kinds of rooms, residential versus commercial spaces, bourgeois privacy, and so on, but the question of a parallel history of the sentence, or of language as such, is not so definitive. Kant, Rousseau, and Stalin have all in one way or another demonstrated that language and its mystic origin do not sit easily in one place in the base-superstructure pair. I still want to comment on the two-way street that Jameson’s story implies here, though. He walks through a building (the Bonaventure hotel, Frank Gehry’s house) and transcodes it as sentence, which implies a parallel fantasy of the poem as building, which Jameson does not go into – poetry is one of the few media he does not devote more than a few pages to in this book. The sonnet has a long history of being conceptualised as space – ‘stanza’ means ‘room’ after all – second only to its history of being conceptualised as a volta in thought, i.e. as dialectical thinking, and Jameson’s ultimate goal here is an account of thinking that is both spatial and dialectical.

With this two-way equivalence of textual architecture in mind, we can maybe recast some of the formal categories that Jameson explicates in this chapter as he grapples with postmodern space. His main one is ‘wrapping,’ which he introduces (or, rather, borrows from architectural discourse) as the postmodern reaction against the figure/ground relationship (in its more Hegelian version) or the text/context relationship (in its humanities inheritance). Frank Gehry’s house is an exemplary study of wrapping – an older, ‘modern’ clapboard house is surrounded by a corrugated steel fence and various glass lines and cubes and other interesting postmodern planes – although in a sense all “quotation,” even the theoretical discourses of explication, annotation, and criticism, participate in this kind of wrapping, where what used to be a technique for positing the autonomy or unity of a quoted object instead lands us in a realm of semi-autonomous regions, where neither wrapped nor wrapper end up determinant (103).

A looser formal category that prefigures wrapping is what Jameson refers to as the “antigravity of the postmodern,” which I want to suggest again has a kind of parallel with postmodern poetry in a way that Jameson doesn’t have time to get into (101). Consider the following (representatively long and cool) sentence:

The most vivid pictorial representation of the process [postmodernism’s relaxation of modernist unities] is surely to be found in the so-called historicism of the postmodern architects, whose various elements—architrave, column, arch, order, lintel, dormer, and dome—begin with the slow force of cosmological processes to flee each other in space, standing out from their former supports, as it were, in free levitation, and, as it were, endowed for a last brief moment with the glowing autonomy of the psychic signifier, as though their secondary syncategoremic function had become for an instant the Word itself, before being blown out into the dust of empty spaces. (100)

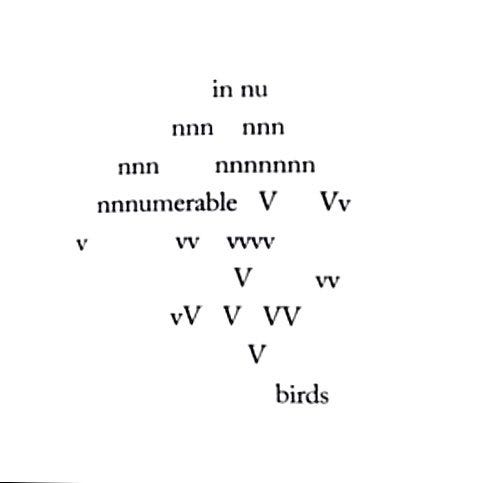

‘As it were’ indeed! To my mind this is like nothing so much as an image of fully exploded free verse poetry, for which the constellation figure is apt. There was, in the modern, an architectural glue (literal and logical) that held together minimal meaningful units in space, and it makes sense to me to look at a concrete or free verse poem and observe the same antigravity at work, the same ungluing of units, as in the poem below:

In this poem, one fully formed and familiar substantive appears at the end (the same logic of reading from top to bottom and left to right appearing to obtain, even if the revelation of the content of the poem causes you to read it again but backwards this time, now recognising mimesis-by-letter) and then applies retroactively an explanatory unity to the poem, a code for returning its gravity to it. We could describe this substantive as a kind of wrapper for the poem, which as a whole consists of the semantic content <innumerable birds> but then uses that content to wrap up its otherwise discontinuous non-semantic letter components – or, rather, the act of reading this poem ends up searching for a wrapper, noting a tension between the semantic and the non-semantic ‘space’ that the form maps out on the page. But in the first place, this poem subjects that semantic content to a non-semantic visual disaggregation, in which each grapheme is unglued and, in Jameson’s words, psychically autonomised.

building / thinking

In the case of the poem, there is a dialectic between the letter and the word, between the meaningfulness of the lexeme and the arbitrariness of the signifier. Or, rather, there is a tension between these two things and the ‘dialectic’ consists in thinking about that contradictory tension and the way it was always present in the word (as a unity perhaps) but in the poem is now split apart and spatialised. This is basically the way Jameson reads postmodern buildings, I think, and he also has an evaluative criteria in mind for the types of dialectical thinking that are either stimulated or arrested in specific cases:

In [the] Portman [hotel,] therefore, reference—the traditional room, the traditional language and category—is brutally dissociated from the newer postmodern space of the euphoric central lobby and left to etiolate and dangle slowly in the wind. The force of Gehry’s structure would then stem from the active dialectical way in which the tension between the two kinds of space is maintained and exacerbated. (120)

In the concluding movement of the chapter, Jameson detours away from the linguistic model that I have expanded upon as poetic and proceeds through the question of representation in general. Let me try a reduction of his argumentative procedure in numbered form here:

the “remarkable aesthetic” of the Russian formalists and others – the idea that the vocation of art is to restimulate perception – “is today meaningless” (121). “It is not clear … why, in an environment of sheer advertising simulacra and images, we should even want to sharpen and renew our perception of those things” (122).

“The slogan ‘representation’ now designates something far more organised and semiotic than older conceptions of habit or Flaubert’s stereotypes … ‘Representation’ is both some vague bourgeois conception of reality and also a specific sign system … and it must now be defamiliarised not by the intervention of great or authentic art but by another art, by a radically different practice of signs” (123).

Jameson is thus suspicious of the stability of the category of perception, or wants to convey that this suspicion is essentially postmodern. We are reminded by Proust that it is the persistence of memory that guarantees a rich and genuine perception of the thing itself, but then Jameson asks us to consider against Proust the extent to which memory is a repository of reified, degraded images, which actually interpose between us and the object.

But then, even more pessimistically and via Derrida, perhaps we were never perceiving directly anyway: “photography and the various machineries of recording and projecting now suddenly disclose or deconceal the fundamental materiality of that formerly spiritual act of vision” (124). Thus we displace the unity of the building in favour of the projection or ‘project’ or ‘blueprint’ of the building that we think we can grasp.

What the Gehry house does, on this point, is block “the choice of photographic point of view, evading the image imperialism of photography securing a situation in which no photograph of this house will ever be quite right” (125).

So Jameson has taken us on a quick journey to the desert of perception, and we have to consider that if “architectural space is a way of thinking and philosophising, of trying to solve philosophical or cognitive problems” (which is a program he discovers in Deleuze’s cinema books), then it must be one that operates with the understanding that both ‘perception’ and ‘representation’ are unreliable, are in fact part of the problem in question.

The problem is still one of representation, and also of representability: we know that we are caught within these more complex global networks, because we palpably suffer the prolongations of corporate space everywhere in our daily lives. Yet we have no way of thinking about them, of modelling them, however abstractly, in our mind’s eye. (127)

And so we return to the problem of what is unthinkable in the postmodern, now cashed out in terms of what is unrepresentable. Some postmodern art works flail about undialectically in this space, ‘representing’ only the dislocation that makes their style both possible and at first intriguing but ultimately unsettling and unsatisfying. Other, better works at least pose the impossibility as an active tension, as a dialectic of thinking-as-spatialisation that would prompt us to sign up to Jameson’s cognitive mapping worker’s education program, or whatever he has in mind for the future of art and practice.

This was most helpful to me, thanking you